BBC

BBCWhen Matthias Huss first visited Rhône Glacier in Switzerland 35 years ago, the ice was just a short walk from where his parents would park the car.

"When I first stepped onto the ice... there [was] a special feeling of eternity," says Matthias.

Today, it's half an hour from the same parking spot and the scene is very different.

"Every time I go back, I remember how it used to be," recalls Matthias, who is now director of Glacier Monitoring in Switzerland (GLAMOS), "how the glacier looked when I was a child."

There are similar stories for many glaciers all over the planet, because these frozen rivers of ice are retreating - fast.

In 2024, glaciers outside the giant ice sheets of Greenland and Antarctica lost 450 billion tonnes of ice, according to a recent World Meteorological Organization report.

That's equivalent to a block of ice 7km (4.3 miles) tall, 7km wide and 7km deep - enough water to fill 180 million Olympic swimming pools.

"Glaciers are melting everywhere in the world," says Prof Ben Marzeion of the Institute of Geography at the University of Bremen. "They are sitting in a climate that is very hostile to them now because of global warming."

Switzerland's glaciers have been particularly badly hit, losing a quarter of their ice in the last 10 years, measurements from GLAMOS revealed this week.

"It's really difficult to grasp the extent of this melt," explains Dr Huss.

But photos - from space and the ground - tell their own story.

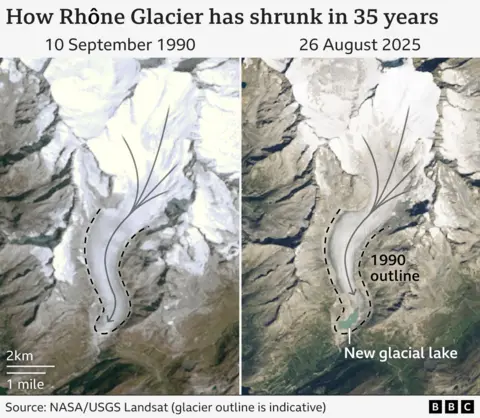

Satellite images show how the Rhône Glacier has changed since 1990, when Dr Huss first visited. At the front of the glacier is a lake where there used to be ice.

Until recently, glaciologists in the Alps used to consider 2% of ice lost in a single year to be "extreme".

Then 2022 blew that idea out of the water, with nearly 6% of Switzerland's remaining ice lost in a single year.

That has been followed by significant losses in 2023, 2024 and now 2025 too.

Regine Hock, professor of glaciology at the University of Oslo, has been visiting the Alps since the 1970s.

The changes over her lifetime are "really stunning", she says, but "what we see now is really massive changes within a few years".

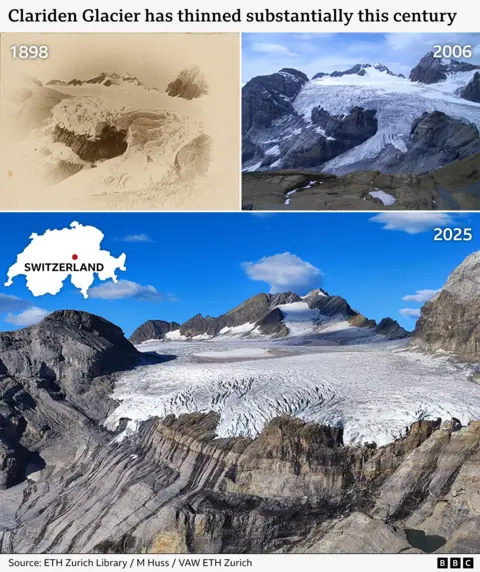

The Clariden Glacier, in north-eastern Switzerland, was roughly in balance until the late 20th Century - gaining about as much ice through snowfall as it lost to melting.

But this century, it's melted rapidly.

For many smaller glaciers, like the Pizol Glacier in the north-east Swiss Alps, it's been too much.

"This is one of the glaciers that I observed, and now it's completely gone," says Dr Huss. "It definitely makes me sad."

Photographs allow us to look even further back in time.

The Gries Glacier, in southern Switzerland near the Italian border, has retreated by about 2.2km (1.4 miles) in the past century. Where the end of the glacier once stood is now a large glacial lake.

In south-east Switzerland, the Pers Glacier once fed the larger Morteratsch Glacier, which flows down towards the valley. Now the two no longer meet.

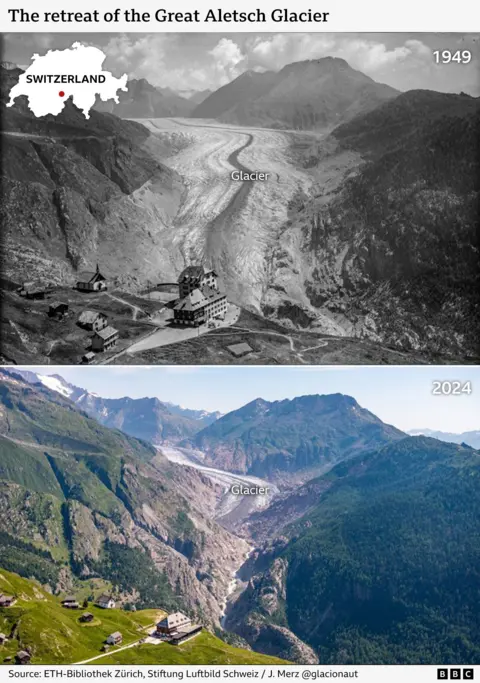

And the largest glacier in the Alps, the Great Aletsch, has receded by about 2.3km (1.4 miles) over the past 75 years. Where there was ice, there are now trees.

Glaciers have grown and shrunk naturally for millions of years, of course.

In the cold snaps of the 17th, 18th and 19th Centuries - part of the Little Ice Age - glaciers regularly advanced.

During this time, many were considered cursed by the devil in Alpine folklore, their advances linked to spiritual forces as they threatened hamlets and farmland.

There are even tales of villagers calling on priests to talk to the spirits of glaciers and get them to move up the mountain.

Glaciers began their widespread retreat across the Alps in about 1850, though the timing varied from place to place.

That coincided with rising industrialisation, when burning of fossil fuels, particularly coal, began to heat up our atmosphere, but it's hard to disentangle natural and human causes that far back in time.

Where there is no real doubt is that the particularly rapid losses of the past 40 years or so are not natural.

Without humans warming the planet - by burning fossil fuels and releasing huge amounts of carbon dioxide (CO2) – glaciers would be expected to be roughly stable.

"We can only explain it if we take into account CO2 emissions," confirms Prof Marzeion.

What is even more sobering is that these large, flowing bodies of ice can take decades to fully adjust to the rapidly warming climate. That means that, even if global temperatures stabilised tomorrow, glaciers would continue to retreat.

"A large part of the future melt of the glaciers is already locked in," explains Prof Marzeion. "They are lagging climate change."

But all is not lost.

Half of the ice remaining across the world's mountain glaciers could be preserved if global warming is limited to 1.5C above "pre-industrial" levels of the late 1800s, according to research published this year in the journal Science.

Our current trajectory is leading us towards warming of about 2.7C above pre-industrial levels by the end of this century – which would see three-quarters of ice lost eventually.

That extra water going into rivers and eventually the oceans means higher sea levels for coastal populations around the world.

But the loss of ice will be particularly acutely felt by mountain communities dependent on glaciers for fresh water.

Glaciers are a bit like giant reservoirs. They collect water as snowfall - which turns into ice - during cold, wet periods, and release it as meltwater during warm periods.

This meltwater helps to stabilise river flows during hot, dry summers - until the glacier disappears.

The loss of that water resource has knock-on effects for all those who rely on glaciers - for irrigation, drinking, hydropower and even shipping traffic.

Switzerland is not immune from those challenges, but the implications are much more profound for the high mountains of Asia, referred to by some as the Third Pole due to the volume of ice.

About 800 million people rely at least partly on meltwater from glaciers there, particularly for agriculture. That includes the upper Indus river basin, which serves parts of China, India, Pakistan, and Afghanistan.

In regions with drier summers, meltwater from ice and snow can be the only significant source of water for months.

"That's where we see the biggest vulnerability," says Prof Hock.

So how do scientists feel when confronted by the future prospects of glaciers in a warming world?

"It's sad," says Prof Hock. "But at the same time, it's also empowering. If you decarbonise and reduce the [carbon] footprint, you can preserve glaciers.

"We have it in our hands."

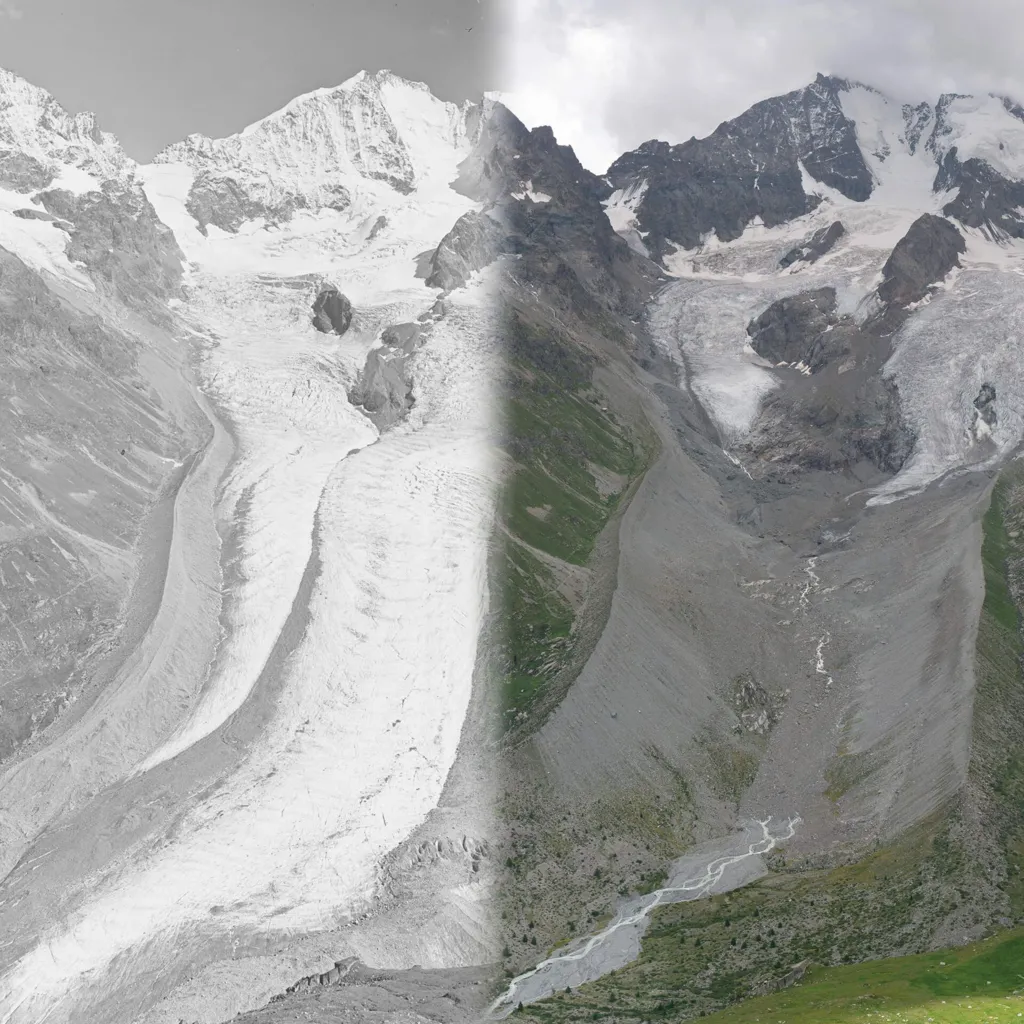

Top image: Tschierva Glacier, Swiss Alps, in 1935 and 2022. Credit: swisstopo and VAW Glaciology, ETH Zurich.

Additional reporting by Dominic Bailey and Erwan Rivault.

Sign up for our Future Earth newsletter to keep up with the latest climate and environment stories with the BBC's Justin Rowlatt. Outside the UK? Sign up to our international newsletter here.