Either the radio had packed up or they were on the wrong wavelength, leaving the men cut off from base in the sweltering heat of Upper Burma. It was March 13, 1944, and they were just two days into a planned 14-day patrol behind enemy lines. Even the battle-hardened jungle fighters, seven officers and 56 men – the vast majority of them Burmese – were feeling the strain of the oppressive heat and their heavy 60lb packs.

Then a few days later, disaster struck when one of the officers, Captain John Gibson, triggered a booby trap. Shrapnel from the blast tore into him, leaving 20 wounds stretching from his left shoulder down to his left heel. Adding to their woes, it was clear the Japanese had launched a major offensive against India, and Allied forces were retreating fast. Even their experienced commander, Major Edgar Peacock, a man who had lived in the Burmese jungles for 18 years before the war, was suffering from severe heat stroke. Nerves were fraying as the men faced the grim reality of their situation.

But Major Edgar Peacock was a hard man and not one to give up easily. As the men of P-Force (Peacock Force) tended to Gibson’s terrible injuries on a ridge overlooking the Kabaw Valley, a plan began to form. Leaving behind non-essential stores and explosives, having washed and dressed Gibson’s wounds and dosed him with morphine, they strapped him to a hastily made bamboo litter and began the exhausting job of carrying him out of the jungle.

These Special Operations Executive, or SOE, men were tough and resourceful and, ultimately, they won through – saving Gibson’s life. He made a full recovery and would complete two more daring missions behind enemy lines with SOE.

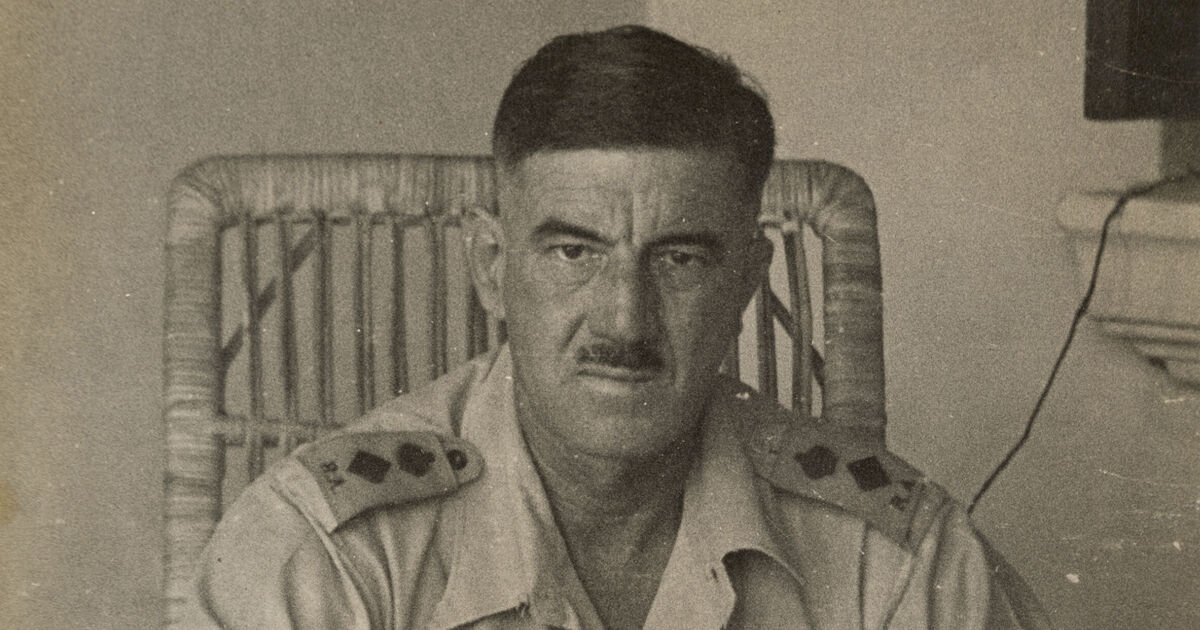

For saving Gibson, Peacock was awarded the Military Cross – a remarkable achievement for a man in his 50s who had fibbed about his age to join the war effort in 1940. Edgar Henry William Peacock was born in Nagpur, India, in February 1893, part of a fourth generation of the Peacock family who had been in India since the 1790s. When he was just 15 years old, tragedy struck when a cholera outbreak orphaned Edgar and his three brothers.

Consequently, raised strictly by his siblings and at boarding school, young Edgar developed into a resilient and independent man. These were exactly the qualities needed for the unconventional role of a Special Forces officer within the highly secretive SOE.

He entered the Indian Forestry Service in 1914, having trained at the Forest Research Institute at Dehradun. He was then posted to Burma. In 1924, Peacock married his wife, Geraldine, in Rangoon, Burma, and then returned to his work as a Forest Officer. This included lengthy tours in the jungle on which his wife and their baby, Joy, accompanied him. In 1932, Peacock retired from the Forestry Service and the family moved to England.

In 1934, the family moved first to South Africa, then to Southern Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe) in 1939. When war was declared against Nazi Germany, Rhodesia as a dominion country became part of the conflict. Peacock enlisted as a private soldier in 1940 and, rapidly rising up the ranks, he was soon a Sergeant, and then sent to officer training school. Having been posted to India, he was then made a Captain and, making the most of his extensive experience of the Burmese jungle, lecturing at the jungle training school.

The British and Indian armies needed to learn fast if they were to reverse the disasters of 1942, when the Japanese army had swept across southeast Asia. In March 1943, Peacock joined the SOE.

While similar to the Chindits under the leadership of Brigadier Orde Wingate in that they operated far behind enemy lines, SOE focused on sabotage, espionage, and raising the indigenous peoples of Burma as guerrilla fighters. However, documents uncovered during research for my book, Jungle Warrior, revealed Peacock and his men went on to fight in the crucial Battle of Imphal from March to July 1944, using aggressive ambush techniques. Until now, it was known only that SOE had deployed propaganda units in this decisive battle, where the Japanese Imperial Army suffered its heaviest losses of the entire war.

Major Peacock was finally pulled out from the front line in May 1944 when he was rushed to hospital for an emergency appendectomy. But more missions with SOE awaited him, this time hundreds of miles behind enemy lines, in the Karenni Hills of southeast Burma.

Using the experienced men Peacock had recruited and trained in the north, parachute landings had been planned to support General Bill Slim’s advancing forces.

And so it was that in late February 1945, shortly after his 53rd birthday, Peacock jumped from a Dakota aircraft and with three Special Groups of highly trained SOE men, began to rally the local Burmese Karen people. They responded in huge numbers, eventually forming a force of some 12,000 guerrillas, organised into four main groups.

Weapons and officer reinforcements were flown in from India, and a sophisticated intelligence network was established across nearly 7,000 square miles of jungle-covered mountains. When General Slim gave the order for Operation Character, Peacock and his men were prepared to strike the enemy hard – and they did.

Before Slim gave that order, though, the Japanese had learnt of enemy parachutists who had established their base on the top of a 7,500ft peak known as Sosiso. This stronghold had to be contested so, in late March, they attacked in Company strength – about 180 combat veterans against Peacock’s hastily raised guerrillas. Some of these recruits had never even fired a gun until days before the Japanese offensive. To Peacock’s surprise, the Japanese “behaved in a very brave but foolish manner”, providing “very good practice” for his band of men.

The struggle lasted 48 hours, before the Japanese finally withdrew, leaving considerable numbers of dead and wounded. Peacock had lost one dead, plus five injured.

With no intention of letting them go only to come back another day, Peacock sent his men after the enemy.

They managed to ambush their foe four times, practically wiping out the entire company, with even the Japanese commanding officer succumbing to his wounds. It was an excellent start to what turned out to be eight months of near-continuous fighting behind enemy lines in this most inhospitable of places. Morale and confidence were high when the Japanese made their next move soon after.

Sosiso overlooked an important road, and the Japanese desperately needed to retreat along it to the town of Toungoo. Once there, they planned to regroup and block the Allied advance on Rangoon.

By now promoted to Lieutenant Colonel, Peacock and his forces launched devastating ambushes on this road to Toungoo, destroying truck after truck packed with enemy soldiers and supplies. They blew up bridges and laid booby traps, creating absolute chaos, just as the founders of SOE had envisioned back in July 1940. The Japanese never reached Toungoo. Instead, the tanks of Slim’s 14th Army did, so the race for Rangoon was still on. For his vital strategic contribution to the Burma campaign, Peacock was awarded an immediate Bar to his Military Cross.

It was now April 1945, but he and his men still faced another six months of intense fighting – plus another concerted effort by the Japanese to remove them from Sosiso in June. This time the fight was much tougher.

The Japanese used a captured Karen levy to guide them towards Sosiso, which led to a platoon outpost being taken and several casualties being inflicted, including the death of a Sergeant Charlesworth. His loss was a blow to Peacock’s command, but even grimmer was the discovery that, once they no longer had a use for him, the Japanese had beheaded the captured Karen guide: 10 days later,when Peacock retook the position, they found “his head lying a few yards from his body” and Charlesworth’s body nearby.

It wasn’t until August 15 that the Japanese finally surrendered after two atomic bombs were dropped on their country, but for the SOE men the brutal jungle war in Burma continued well into September.

By then, Operation Character as a whole had accounted for nearly 12,000 Japanese, and took the surrender of 11,000 more –

for the cost of only 22 SOE men. For his sustained and exceptional leadership and bravery in the face of the enemy throughout this extended period, Peacock was awarded the Distinguished Service Order.

Having spent almost his entire war since April 1943 fighting behind enemy lines, Peacock returned to Rhodesia in 1946. He died there aged 62 in March 1955, having suffered PTSD and wartime injuries, including a damaged eye.

Peacock should be remembered as a true Jungle Warrior of the Second World War. It’s fitting we finally remember his contribution to the Burma campaign as we mark the 80th anniversary of VJ Day, and he at last gains the recognition he deserves as Britain’s greatest SOE commander.

● Dr Richard Duckett is author of Jungle Warrior: Britain’s Greatest SOE Commander (Chiselbury Publishing, £22)