Kevin Church/BBC

Kevin Church/BBCPerched on top of Santorini's sheer cliffs is a world-famous tourist industry worth millions. Underneath is the fizzing risk of an almighty explosion.

A huge ancient eruption created the dreamy Greek island, leaving a vast crater and a horse-shoe shaped rim.

Now scientists are investigating for the first time how dangerous the next big one could be.

BBC News spent a day on board the British royal research ship the Discovery as they searched for clues.

Kevin Church/BBC

Kevin Church/BBCJust weeks before, nearly half of Santorini's 11,000 residents had fled for safety when the island shut down in a series of earthquakes.

It was a harsh reminder that under the idyllic white villages dotted with gyros restaurants, hot tubs in AirBnB rentals, and vineyards on rich volcanic soil, two tectonic plates grind in the Earth's crust.

Prof Isobel Yeo, an expert on highly dangerous submarine volcanoes with Britain's National Oceanography Centre, is leading the mission. Around two-thirds of the world's volcanoes are underwater, but they are hardly monitored.

"It's a bit like 'out of sight, out of mind' in terms of understanding their danger, compared to more famous ones like Vesuvius," she says on deck, as we watch two engineers winching a robot the size of a car off the ship's side.

This work, coming so soon after the earthquakes, will help scientists understand what type of seismic unrest could indicate a volcanic eruption is imminent.

Santorini's last eruption was in 1950, but as recently as 2012 there was a "period of unrest", says Isobel. Magma flowed into the volcanoes' chambers and the islands "swelled up".

Kevin Church/BBC

Kevin Church/BBC"Underwater volcanoes are capable of really big, really destructive eruptions," she says.

"We are lulled into a sense of false security if you're used to small eruptions and the volcano acting safe. You assume the next will be the same - but it might not," she says.

The Hunga Tunga eruption in 2022 in the Pacific produced the largest underwater explosion ever recorded, and created a tsunami in the Atlantic with shockwaves felt in the UK. Some islands in Tonga, near the volcano, were so devastated that their people have never returned.

Beneath our feet on the ship, 300m (984ft) down, are bubbling hot vents. These cracks in the Earth turn the seafloor into a bright orange world of protruding rocks and gas clouds.

"We know more about the surface of some planets than what's down there," Isobel says.

The robot descends to the seabed to collect fluids, gases and snap off chunks of rock.

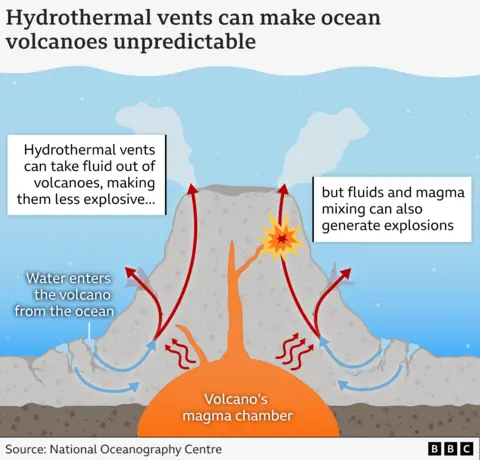

Those vents are hydrothermal, meaning hot water pours out from cracks, and they often form near volcanoes.

They are why Isobel and 22 scientists from around the world are on this ship for a month.

So far, no-one has been able to work out if a volcano becomes more or less explosive when sea water in these vents mixes with magma.

"We are trying to map the hydrothermal system," Isobel explains. It's not like making a map on land. "We have to look inside the earth," she says.

The Discovery is investigating Santorini's caldera and sailing out to Kolombo, the other major volcano in this area, about 7km (4.3 miles) north-east of the island.

The two volcanoes are not expected to erupt imminently, but it is only a matter of time.

The expedition will create data sets and geohazard maps for Greece's Civil Protection Agency, explains Prof Paraskevi Nomikou, a member of the government emergency group that met daily during the earthquake crisis.

Tom Ingham/BBC

Tom Ingham/BBCShe is from Santorini, and grew up hearing about past earthquakes and eruptions from her grandfather. The volcano inspired her to become a geologist.

"This research is very important because it will inform local people how active the volcanoes are, and it will map the area that will be forbidden to access during an eruption," she says.

It will reveal which parts of the Santorini sea floor are the most hazardous, she adds.

These missions are incredibly expensive, so Isobel crams in experiments night and day as the scientists work in 12-hour shifts.

John Jamieson, a professor at Canada's Memorial University in Newfoundland, shows us volcanic rocks extracted from the vents.

"Don't pick that one up," he warns. "It's full of arsenic."

Pointing to another that looks like a black and orange meringue with gold dusting, he explains: "This is a real mystery - we don't even know what it is made of."

These rocks tell the history of the fluid, temperature and material inside the volcano. "This is a geological environment different to most others - it's really exciting," he says.

But the mission's beating heart is a dark shipping container on deck where four people stare at screens mounted on a wall.

Using a joystick that wouldn't look out of a place on a gaming console, two engineers drive the underwater robot. Isobel and Paraskevi trade theories about what is in a pool of fluid that the robot has found.

They have recorded very small earthquakes around the volcano, caused by fluid moving through the system and causing fractures. Isobel plays us an audio recording of the fractures reverberating. It sounds like the bass in a nightclub being amped up and down.

They identify how fluid moves through rocks by pulsing an electromagnetic field into the earth.

This is creating a 3D map that shows how the hydrothermal system is connected to the volcano's magma chamber where an eruption is generated.

"We are doing science for the people, not science for the scientists. We are here to make people feel safe," Paraskevi says.

The recent earthquake crisis in Santorini highlighted how exposed the island's residents are to the seismic threats and how reliant they are on tourism.

Back on dry land, photographer Eva Rendl meets me in her favourite location for wedding shoots. When the so-called swarm of earthquakes hit in February, she left the island with her daughter.

Kevin Church/BBC

Kevin Church/BBC"It was really scary, as it got more and more intense," she says.

She's back now but business is slower. "People have cancelled bookings. Normally I start shoots in April but my first job isn't until May," Eva says.

In the main square of Santorini's upmarket town Oia, British-Canadian tourist Janet tells us six of her group of 10 cancelled their holiday.

She believes more accurate scientific information about the likelihood of earthquakes and volcanoes would help others feel more reassured about visiting.

"I get the Google alerts, I get the scientists' alerts, and it helps me feel safe," she said.

Kevin Church/BBC

Kevin Church/BBCBut Santorini will always be a dream destination. In Imerovigli, we see two people climbing onto the curved rooftops to get the perfect shot.

The couple - married for just 15 minutes - travelled from Latvia and were not put off by the island's underwater risks.

"Actually we wanted to get married by a volcano," Tom says, his bride Kristina by his side.