BBC/Aamir Peerzada

BBC/Aamir PeerzadaWhen investigators smashed through a hastily built wall, they uncovered a set of secret jail cells.

It turned out to be a freshly bricked-up doorway – an attempt to hide what lurked behind.

Inside, off a narrow hallway, were tiny rooms to the right and left. It was pitch-black.

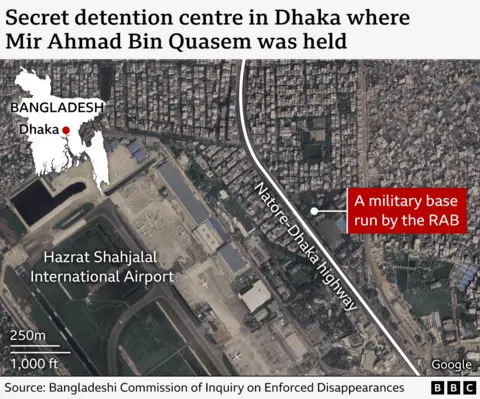

The team may never have found this clandestine jail – a stone's throw from Dhaka's International Airport – without the recollections of Mir Ahmad Bin Quasem and others.

A critic of Bangladesh's ousted leader, he was held there for eight years.

He was blindfolded for much of his time in the prison, so he leaned on the sounds he could recall - and he distinctly remembered the sound of planes landing.

That was what helped lead investigators to the military base near the airport. Behind the main building on the compound, they found the smaller, heavily guarded, windowless structure made of brick and concrete where detainees were kept.

It was hidden in plain sight.

BBC/Aamir Peerzada

BBC/Aamir PeerzadaInvestigators have spoken to hundreds of victims like Quasem since mass protests ousted Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina's government last August, and inmates in the jails were released. Many others are alleged to have been killed unlawfully.

The people running the secret prisons, including the one over the road from Dhaka airport, were largely from an elite counter-terrorism unit, the Rapid Action Battalion (RAB), acting on orders directly from Hasina, investigators say.

"The officers concerned [said] all the enforced disappearance cases have been done with the approval, permission or order by the prime minister herself," Tajul Islam, the chief prosecutor for the International Crimes Tribunal of Bangladesh, told the BBC.

Hasina's party says the alleged crimes were carried out without its knowledge, that it bears no responsibility and that the military establishment operated alone - a charge the army rejects.

Seven months on, Quasem and others may have been released, but they remain terrified of their captors, who are serving security force members and are all still free.

Quasem says he never leaves home without wearing a hat and mask.

"I always have to watch my back when I'm travelling."

He slowly walks up a flight of concrete steps to show the BBC where he was kept. Pushing through a heavy metal door, he bends his head low and goes through another narrow doorway into "his" room, the cell where he was held for eight years.

"It felt like being buried alive, being totally cut off from the outside world," he tells the BBC. There were no windows and no doors to natural light. When he was inside, he couldn't tell between day or night.

Quasem, a lawyer in his 40s, has done interviews before but this is the first time he has taken the media for a detailed look inside the tiny cell where he was held.

Viewed by torchlight, it is so small an average-sized person would have difficulty standing up straight. It smells musty. Some of the walls are broken and bits of brick and concrete lie strewn on the ground - a last-ditch attempt by perpetrators to destroy any evidence of their crimes.

"[This] is one detention centre. We have found that more than 500, 600, 700 cells are there all through the country. This shows that this was widespread and systematic," says Islam, the prosecutor, who accompanied the BBC on the visit to the jail.

Quasem also clearly remembers the faint blue tiles from his cell, now lying in pieces on the floor, which led investigators to this particular room. In comparison to the cells on the ground floor, this one is much larger, at 10ft x 14ft (3m x 4.3m). There is a squatting toilet off to one side.

BBC/Aamir Peerzada

BBC/Aamir PeerzadaIn painful detail, Quasem walks around the room, describing how he spent his time during his years in captivity. During the summers, it was unbearably hot. He would crouch on the floor and put his face as close to the base of the doorway as he could, to get some air.

"It felt worse than death," he says.

Coming back to relive his punishment seems cruel. But Quasem believes it is important for the world to see what was done.

"The high officials, the top brass who aided and abetted, facilitated the fascist regime are still in their position," he says.

"We need to get our story out, and do whatever we can to ensure justice for those who didn't return, and to help those who are surviving to rehabilitate into life."

Previous reports said he was kept inside a notorious detention facility - known as Aynaghor, or "House of Mirrors" - inside the main intelligence headquarters in Dhaka, but investigators now believe there were many such sites.

Quasem told the BBC he spent all his detention at the RAB base, apart from the first 16 days. Investigators now suspect the first site was a detective branch of police in Dhaka.

He believes he was disappeared because of his family's politics. In 2016 he'd been representing his father, a senior member of the country's largest Islamist party, the Jamaat-e-Islami, who was on trial and later hanged.

Handout

HandoutFive other men the BBC spoke to described being taken away, blindfolded and handcuffed, kept in dark concrete cells with no access to the outside world. In many cases they say they were beaten and tortured.

While the BBC cannot independently verify their stories, almost all say they are petrified that one day, they might bump into a captor on the street or on a bus.

"Now, whenever I get into a car or I'm alone at home, I feel scared thinking about where I was," Atikur Rahman Rasel, 35, says. "I wonder how I survived, whether I was really supposed to survive.

He says his nose was broken and his hand is still painful. "They put handcuffs on me and beat me a lot."

Getty Images

Getty ImagesRasel says he was approached by a group of men outside a mosque in Dhaka's old city last July, as anti-government protests raged. They said they were from law enforcement and he had to go with them.

The next minute, he was taken into a grey car, handcuffed, hooded and blindfolded. Forty minutes later, he was pulled out of the car, taken into a building and put in a room.

"After about half an hour, people started coming in one by one and asking questions. Who are you? What do you do?" Then the beatings started, he says.

"Being inside that place was terrifying. I felt like I would never get out."

Rasel now lives with his sister and her husband. Sitting on a dining chair in her flat in Dhaka, he describes his weeks in captivity in detail. He speaks with little emotion, seemingly detached from his experience.

He too believes his detention was politically motivated because he was a student leader with the rival Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP), of which his father was a senior member. His brother, who lived abroad, would frequently write social media posts critical of Hasina.

Rasel says there was no way of knowing where he was held. But after watching interim leader Muhammad Yunus visiting three detention centres earlier this year, he thinks he was kept in Agargaon district in Dhaka.

Bangladesh Chief Advisor Office of Interim Government via AFP

Bangladesh Chief Advisor Office of Interim Government via AFP AFP

AFPIt was an open secret that Hasina had no tolerance for political dissent. Criticising her could get you "disappeared" without a trace, former detainees, opponents and investigators say.

But the total number of people who went missing may never become clear.

A Bangladeshi NGO that has tracked enforced disappearances since 2009 has documented at least 709 people who were forcibly disappeared. Among them, 155 people remain missing. Since the Commission of Inquiry on Enforced Disappearances was created in September, they have received more than 1,676 complaints from alleged victims and more people continue to come forward.

But that doesn't represent the total number, which is believed to be much higher.

It is through speaking to people like Quasem that Tajul Islam is able to build a case against those responsible for the detention centres, including Sheikh Hasina.

Despite being held at different sites, the narrative of victims is eerily similar.

Mohammad Ali Arafat, spokesperson for Hasina's Awami League party, denies any involvement. He says if people were forcibly disappeared, it was not done under the direction of Hasina - who remains in India, where she fled - or anyone in her cabinet.

"If any such detention did occur, it would have been a product of complex internal military dynamics," said Arafat. "I see [no] political benefit for the Awami League or for the government to keep these people in secret detention."

The military's chief spokesman said it "has no knowledge of the things being implied".

"The army categorically denies operating any such detention centres," Lt Col Abdullah Ibn Zaid told the BBC.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesTajul Islam believes the people held in these prisons are evidence of Awami League involvement. "All the people who were detained here were from different political identities and they just raised their voice against the previous regime, the government of that time, and that is why they were brought here."

To date they have issued 122 arrest warrants, but no one has yet been brought to justice.

Which is why victims like Iqbal Chowdhury, 71, believe their lives are still in danger. Chowdhury wants to leave Bangladesh. For years after he was released in 2019, he didn't leave his house, not even to go to the market. Chowdhury was warned by his captors never to speak of his detention.

"If you ever reveal where you were or what happened, and if you are taken again, no one will ever find or see you again. You will be vanished from this world," he says he was told.

Accused of writing propaganda against India and the Awami League, Chowdhury says that is why he was tortured.

"I was physically assaulted with an electric shock as well as being beaten. Now one of my fingers is heavily damaged by the electric shock. I lost my leg's strength, lost physical strength." He remembers the sound of others being physically tortured, grown men howling and crying in agony.

"I am still scared," says Chowdhury.

BBC/Neha Sharma

BBC/Neha SharmaRahmatullah, 23, is also terrified. "They took away a year and a half of my life. Those times won't ever be returned," he says. "They made me sleep in a place where a human being should not even be."

On 29 August 2023, he was taken from his home at midnight by RAB officers, some in uniform and others dressed in plain clothes. He was working as a cook in a neighbouring town while training to be an electrician.

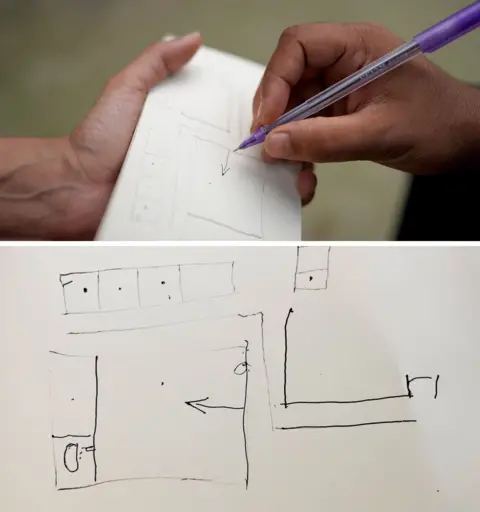

After repeated interrogations, it became clear to Rahmatullah he was being forcibly detained for his anti-India and Islamic posts on social media. Using a pen and paper, he draws the layout of his cell, including the open drain he would use to relieve himself.

"Even thinking about that place in Dhaka makes me feel horrible. There was no space to lie down properly, so I had to sleep being curled up. I couldn't stretch my legs while lying down."

BBC/Neha Sharma

BBC/Neha SharmaThe BBC also interviewed two other former detainees – Michael Chakma and Masrur Anwar – to corroborate some of the details about the secret prisons and what is alleged to have gone on inside them.

Some of the victims live with physical scars from their detentions. All of them talk about the psychological torment that follows them everywhere they go.

Bangladesh is at a pivotal moment in its history as it tries to rebuild after years of autocratic rule. A crucial test of the country's progress towards democracy will be its ability to hold a fair trial for the perpetrators of these crimes.

Islam believes it can, and must happen. "We must stop the recurrence of this type of offence for our future generations. And we have to do justice for the victims. They suffered a lot."

Standing in what remains of his concrete cell, Quasem says a trial must take place as soon as possible so the country can close this chapter.

It's not so simple for Rahmatullah.

"The fear has not gone away. The fear will remain until I die."